Mozambiques economic structure will soon change, as ‘multiplier effects’ of mega projects lead to a more diversified industrial base

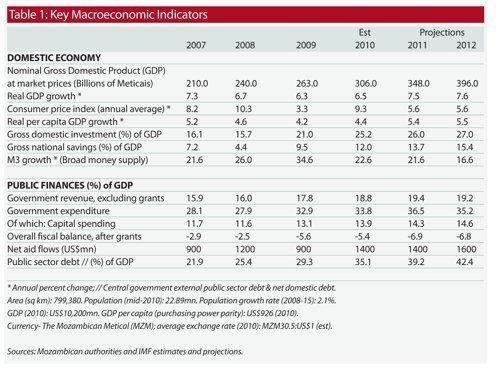

Mozambique is rapidly developing into a ‘project driven’ market with lucrative openings for project financiers, engineering, procurement and construction companies, as well as general services providers. The coming onstream of projects in the natural resources sector will increase tax revenues and reduce heavy reliant on foreign aid over the medium term. In 2007-09, the total value of projects approved by the Investment Promotion Agency (CPI) totalled $14.9bn (see Table 1).

The World Bank noted: “If a significant proportion of these projects are realised and well managed, they would have the potential to transform the socio-economic environment in Mozambique and create many thousands of new jobs. However, all authorised projects are not implemented while others are realised over several years’ time.”

Among large projects where works have already started include the $500mn railway line connecting the northern Nacala port with coalmines of Moatize; the construction of Nacala International Airport in Nampula province by Brazilian firm Odebretch; the rehabilitation of Beira port, which also serves landlocked Malawi and Zimbabwe; an expansion of hydroelectric production at the Cahora-Bassa dam in central Mozambique; the building of a power line backbone between the Cahora-Bassa Dam and Maputo; and the upgrade of the road network (currently only one-third of Mozambique’s roads are paved).

About $1bn is allocated for electrification programme – with new power stations planned across the country.

Coal mining

Other mega schemes in the pipeline are the $5bn coal-mining projects in northern Tete province by China’s Kingho miner; a huge oilrefinery (estimated cost $5bn) in Nampula province – where the US-based Ayr Logistics has expressed an interest; and new generation capacity of 6,000 megawatts (MW) planned in Tete province, as well as 2,400 MW from the Mpanda Uucua hydro plant on the Zambezi River. Also, a transmission line is planned to connect the vast northern and southern regions.

The most successful foreign venture to date is the $2.5bn Mozal aluminium smelter – just 17km from Maputo. The smelter uses Aluminium Pechiney AP35 technology to produce over 500,000 metric tonnes a year aluminium ingots and is supplied with alumina by the Worsley refinery in Western Australia.

The shareholders are BHP Billiton, Japan’s Mitsubishi Corporation, Industrial Development Corporation of South Africa and the Mozambique government – holding 47 per cent, 25 per cent, 24 per cent and 3.9 per cent stakes, respectively, in a project that has made Mozambique one of the world’s leading exporters of aluminium.

In 2009, foreign-owned projects led by Mozal Aluminium accounted for 12 per cent of GDP.

Mozambique is contemplating new financing options to boost infrastructure projects, including private finance initiative (PFI), public-private partnerships (PPPs), external sovereign bond issues, syndicated loans and co-financing from bilateral export credit agencies.

The authorities should be cautious that non-concessional borrowing does not undermine fiscal and debt sustainability. Private investment is expected to increase significantly in mining, energy, refining and infrastructure as series of mega-projects are implemented.

Popular FDI hotspot

Mozambique’s image as an investment destination has improved markedly, leading to a jump in foreign direct investment (FDI). The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) figures put total net FDI over 2000-09 at $3.5bn. Meanwhile, inward FDI stock has surged from $1.25bn in 2000 to $4.69bn in 2009. Aluminum production, energy and extractive industries have received large chucks of inward investment. The Bank of Mozambique (central bank) noted FDI has a positive impact on “job creation, promotion of technological progress and the improvement of the external position, both via exports and by replacing imports.”

The country has several comparative advantages that appeal to strategic investors. Those include its close proximity to Africa’s No.1 market (South Africa), 2,750 km of Indian Ocean coastline, rich mineral resources coupled with vast unused arable land. Thus, its unique geographical location in southern Africa leverages Mozambique’s role in regional trade (especially with its landlocked neighbours) as well as providing scope to attract ‘vertical’ or asset-seeking FDI from transnational corporations (TNCs), mainly in the manufacturing sector.

Mozambique offers good conditions for TNCs to base their southern Africa operations and access the wider Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) markets of 263mn customers worth some $467bn. The surging middle-classes and hence increased purchasing power in South Africa and elsewhere offers lucrative marketing opportunities to TNCs.

Under the 2009 Code of Fiscal Benefits, 10 categories of investment are exempt from customs duty and VAT, as well as enjoy partial tax holidays and other benefits like accelerated depreciation and deductions for professional training.

These include investment in public infrastructure, rural commerce/industry, manufacturing/assembly industries, agriculture/fisheries, hotels/tourism, science/technology, parks, mega-projects, industrial free zones, and special economic zones. The minimum capital threshold to take advantage of any guarantees and fiscal incentives is $50,000 for foreign investments.

Diversified mining industry

Sizeable foreign capital and technical expertise have gone into building a diversified mining industry. Brazilian giant Vale, the world’s biggest iron ore miner, and Irelandbased Kenmare Resources are investing heavily in the coal and titanium sectors. Vale is developing the Moatize basin – ranked among the few unexploited regions for coal reserves – in a project costing $1.5bn and projected to yield 40mn tonnes of coal per/year, while Kenmare Resources’ $450mn venture focuses on the Moma titanium mine (the world’s largest).

Riversdale Mining of Australia and India’s Tata Steel also plan to invest $800mn in the Benga coal mine, which could produce 20mn tonnes/year in the long-term. The country’s total coal reserves are estimated at 23bn tonnes. Mineral exports could rise by $1bn annually when the Moatize coalmine reaches full production. According to official sources, eight new coalmines will be onstream by 2016, of which two should be operational by mid-2011.

Opportunities also exist for mining majorsand juniors to capitalise on ‘untapped’ deposits of gold, precious and semi-precious stones, iron ore, bauxite, beryllium, tantalite, copper, lead and even uranium. The modernised mining code and regulations have strengthened Mozambique’s mining legislation on a level with global best practice.

The new mining cadastre (with four regional offices) has contributed to the processing of about 1,000 licenses to date. Mozambique’s modest but rising gas reserves have attracted major foreign energy groups, Italy’s ENI, Norway’s Statoil, Malaysia’s Petronas and US independent Anadarko Petroleum.

Total natural gas reserves are put at 14 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) – surpassing both the UK’s (10.3 Tcf) and Brazil’s (12.7 Tcf). The stateowned Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetos (ENH) has allocated $1.4bn for exploration & development works over 2009-11. The government is now planning the privatisations of electricity, telecoms, ports and the railways. Among commercially viable entities that could attract strategic foreign investors include ENH (responsible for exploration and processing of gas), Linhas Aéreas de Moçambique (LAM, the national carrier) and Portos e Caminhos de Ferro de Mocambique (the parastatal in charge of the railways and five ports).

Future challenges

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects GDP growth to average 7.8 percent/year between 2011 and 2015, underpinned by new large projects and spill-offs from associated services and construction sectors, as well as increased agriculture output. But broader activity outside capitalintensive export sectors remains below potential. While labour-intensive manufacturing and commercialisation of agriculture (including agro-processing) have yet to take-off, which can raise the country’s productive base.

Mozambique has successfully concluded first-generation reforms that provided macro-stability and strengthened its resilience to exogenous shocks. The World Bank commended: “Mozambique has emerged from decades of conflicts to become one of Africa’s best-performing economies.”

The country has enjoyed a remarkable recovery - the highest growth rate among African oil-importers. Nonetheless, concerted efforts are needed to achieve ‘quality growth’ and catch up with Asian economies by implementing micro-reforms.

Chief among these are simplifying product and services market regulations, raising human capital and technical capacities, as well as fostering a more conducive business climate.

Developing a skill-based economy, greater diversification and most importantly, closing the ‘infrastructure gap’ is critical to improve national competitiveness.

The Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostics (AICD) estimates that Mozambique needs to spend $1.7bn a year on public infrastructure over the next decade to catch up with other developing nations.