Page 1 of 2As private wealth increases across the continent, and consumer-driven industry growth outpaces non-African regions, so regulation of investible assets gains critical importance

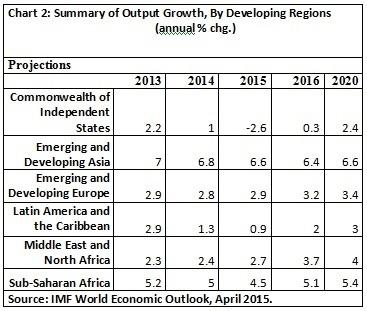

The latest projections from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) show that sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remains among the world’s fastest-growing regions, despite weaker oil and commodity prices, uncertain external financing conditions and the Ebola epidemic in worst-affected countries (Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea). The region has enjoyed strong economic growth of 5.2percent on average over 2010-2014 driven by investments in mining and infrastructure, as well as buoyant private consumption in many countries.

Africa, the home to nearly one billion people is now beginning to take its rightful place at the table of global prosperity. The expanding middle-class population is creating demand for construction and services industry. Notwithstanding the challenges, opportunities for businesses are plentiful.

The World Bank commented, “Despite strong headwinds and new challenges, sub-Saharan Africa is still experiencing growth. And with challenges come opportunities.”

The IMF and the World Bank expect a slowdown during 2015; however, there are significant differences across regions. The downturn in international petroleum markets has affected oil-exporting countries (especially Angola and Nigeria, SSA’s largest and third-largest economies), which supply three-fourths of Africa’s oil output. Real GDP growth will falter as fiscal consolidation dampens economic activity (Table1) – with public investment bearing the brunt of ongoing fiscal tightening in oil-producing countries.

With limited buffers, the Nigerian authorities are cutting capital spending, whilst adjusting monetary and exchange rate policies to relieve pressures on the Naira. Lower capital spending also affects Nigeria’s non-oil growth, which averaged 7.8 per cent over 2013-14. Crude prices should rebound but will remain below the US$100/barrel level of recent years.

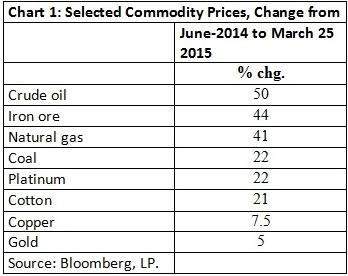

On the one hand, oil-importing countries are still growing briskly, notably DR Congo, Ethiopia, Cote d’Ivoire, Tanzania, Rwanda and Kenya. Excluding South Africa, which is hindered by mining strikes and electricity supply constraint, real GDP growth of oil-importers is predicted at 5.9 and 6.6 per cent, respectively this year and next. However, the impact of cheap fuel is partly offset by lower prices of other commodities that they export. Since June 2014, the price of iron ore, coal, platinum, cotton, copper, and gold have dropped by 44; 22; 22; 21; 7.5; and five per cent, respectively (Chart1).

Output in three Ebola-hit countries of sub-West Africa has contracted due to severe disruptions in agriculture and services and the postponement of mining development projects. The situation is grim in Sierra Leone, where main iron ore mines have ceased operations and GDP growth is likely to drop by 13 per cent – compared to robust growth of 20 per cent in 2013.

Greater resilience

Greater resilience

Low inflation, reduced levels of public debt, and adequate reserve levels have helped to shield much of the region from global downturn in recent years. Weak energy and food prices have helped underpinned generally subdued inflation environment, which could allow countries dealing with tepid growth to adopt more lax macroeconomic stance. Monetary policy has been tightened in some places where currencies have come under pressure.

The eight oil-exporters are tightening fiscal policy that should partially offset the impact of depleting revenues, but budget deficits are still projected to widen by about 3/4 of percentage point of GDP relative to 2014. Government debt is forecast to grow by some two percentage points of GDP, with more substantial increases in few countries (notably Equatorial Guinea).

Current account deficits are expected to widen significantly for oil-exporters, with large increases in Chad and Equatorial Guinea. Conversely, among most oil-importers, current account balances are expected to improve. However, for a few resource exporters, including Namibia and Congo DRC, the decline in other commodity prices could have bigger spillovers than lower oil prices – hence leading to deteriorating current account balances.

External influences

In today’s global village, Africa’s prosperity is mainly tied to outside factors. Among major trade partners, the weakness in Eurozone and Japan poses downside risks to global recovery. Similarly, the slowdown of China’s investment-led growth in 2015-16 could reduce demand for raw material exports – driving regional growth lower and widening fiscal deficits, whilst curtailing foreign direct investment (FDI) in natural resources and infrastructure.

The U.S. dollar’s appreciation versus the euro in recent months has regional implications, where most Francophone countries have formal pegs to the euro and a few others peg informally to the dollar. Most national currencies have depreciated significantly against the greenback this year. A stronger dollar harms the competitiveness of economies (mostly oil-exporters) that are broadly pegged to the dollar. “Some actually benefit and some suffer as a result of the dollar appreciation – they benefit because you get dollar pricing for the oil that you export and it sometimes compensates a little bit for the decline in oil prices,” explained IMF managing director Christine Lagarde.

In the near term, currency weaknesses increase the cost of imports, much of which is typically related to investment, with adverse effects on productivity growth. Furthermore, a depreciated exchange rate increases debt service costs where dollar-denominated debts represent a larger share of total public debt – subsequently resulting in deteriorating balance sheet positions of banks and private sector entities. Finally, in some countries, depreciation can fuel rising consumer prices, thus curtailing domestic demand.